For the best part of two decades trombonist, composer and arranger Raph Clarkson has been an integral part of the UK jazz scene, winning much acclaim for adventurous album releases such as Soldiering On, Resolute, and This Is How We Grow. Clarkson’s writing for the exciting 15-piece orchestra Dissolute Society draws on many genres, from jazz to progressive rock to classical music, but is ultimately defined by the artist’s strength of character and imagination. Vibrantly performed and at times intricately structured, Clarkson’s music explore themes as varied as family history, friendship, grief and hope, and is testament to his proven ability to bring as much emotional depth as creative breadth to both stage and studio.

While that recent flurry of albums reflects Clarkson’s steady artistic growth the seeds were planted long ago. The son of two string players, he knew in his childhood that he was destined to have music in his life in some capacity. Today, looking back, he is well aware of the specific motivation that led him to become an artist. “I realized I wanted to be doing it in as direct and visceral a way as possible,” he reflects. “I absolutely loved the aspect of music making that is social, forging connections with other people, enjoying each other’s company while playing together.”

That sense of collective energy certainly runs through Clarkson’s output, and he would be the first to acknowledge the pivotal role played by a number of influential personalities in his own development. Now living in Bristol, a city with a long, rich history of jazz and improvised music, Clarkson was greatly inspired by a local figure who went on to achieve international renown, pianist Keith Tippett, and with whom the trombonist studied while, firstly, a child, and then a teenager at Dartington International Summer School. “His deeply passionate, spiritual, democratic approach and his magical introductions to the world of free improvisation have always stayed with me,” says Clarkson, who also had the chance to complete a course at the University of York with another British piano icon, John Taylor. “I absolutely fell in love with his music and that of Kenny Wheeler. He was also such a warm and gentle teacher who inspired quiet curiosity about jazz and improvising, while simultaneously being totally fierce and committed and passionate and powerful in his improvising.”

It comes as no surprise that there are similar qualities in Clarkson’s own body of work, which is notable for stylistic range as well as high standards of performance.

He was a member of World Service Project, a boisterous and subversive ensemble that won a large following throughout the UK and Europe in the 2010s, and was also part of the massed ranks of Chaos Orchestra, the ambitious outfit led by the award-winning trumpeter Laura Jurd, whom Clarkson also counts as an influence. He has since worked with Jurd on her “Stepping Back, Jumping In” ensemble record and is soon to record with her again as part of a collaboration with the Paul Dunmall Quartet.

Other collaborators include producers Steve Baker and Sonny Johns, bassist and producer Riaan Vosloo, saxophonist Chris Williams and keyboardist Phil Merriman, as well as creative commissions, collaborations and workshop facilitation projects with ensembles such as The Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, Sinfonia Viva, the London Sinfonietta and the Britten Sinfonia . Clarkson’s career to date has been marked by the conviction that much is to be gained by working with other artists as well as fulfilling one’s own vision.

“There is the deep thrill of bringing something new into the world, the process of guiding ideas that knock around the mind and on scraps of paper into sounds that exist in the world,” Clarkson explains. “It’s the satisfaction of finding just the right sounds to express an idea, a feeling to tell a story that until that point was intangible or on the tip of one’s tongue. And then the joy of sharing that with others and hearing other humans bring those sounds to life is the next stage beyond me and a piano, or notebook voice recordings or audio mock-ups. The stage where a group of musicians interprets and makes those musical ideas I suggested their own is also super exciting.

“When I’m truly on my own with music, working stuff out at the piano or singing and playing for my own enjoyment, the most satisfying thing is probably getting into a true ‘flow’ state, a mindful state where I am completely present. And that is something I also strive to do in live performance and collaboration with others.”

Like any artist with a degree of intellectual curiosity Clarkson has sought to explore new thematic avenues in his work. His latest project Songs For Childhood, started at the beginning of the pandemic in 2020, is inspired by and dedicated to young people and has a playful, often uplifting character in line with the subject matter. “I’m increasingly interested in aspects of childhood and child development that often intersect with my work as a workshop leader,” he explains. “I’m thinking around trauma-informed practice and speech development, the way we process our environments, the way we function in groups vs how we function individually, and there’s also the nature of play in childhood and how this can contribute to our lives as adults. There is probably a political element mixed into this; something to do with true democracy and people-led ideas, as opposed to any authoritarian approaches to organising human life.”

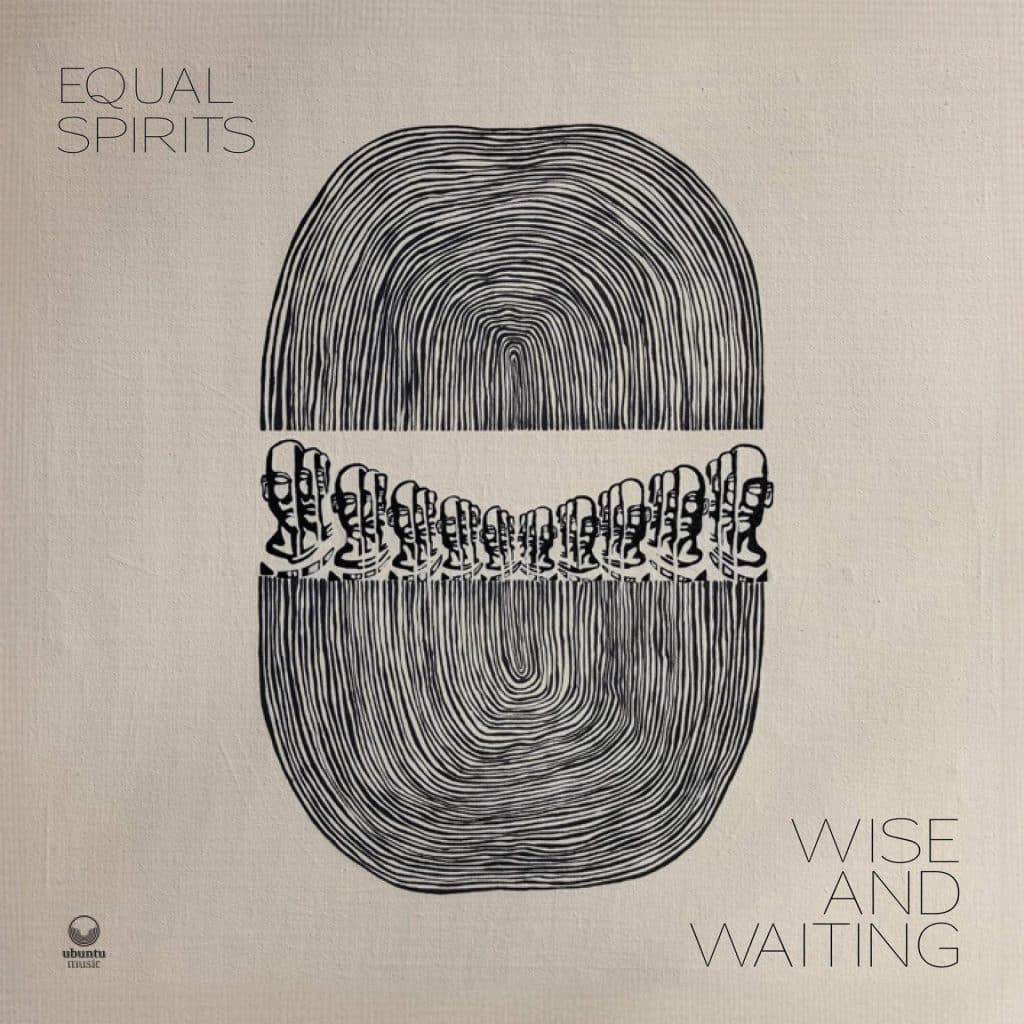

These thoughts are grist to Clarkson’s artistic mill. The theme of childhood is also fuelling future projects such as a ‘weird, bonkers musical’ but there is no shortage of other ideas in the pipeline. He aims to write more music for both orchestras and individuals, and, perhaps most excitingly, has also recorded an ensemble called Equal Spirits, which is a collaboration with musicians from South Africa that celebrates the enormous contribution to British jazz made by icons such as Louis Moholo-Moholo.

Clarkson is proving to be a dynamic and forward-thinking artist who is not placing any limits on his activity, to the extent that disciplines outside of music, such as visual art and mindfulness, have also featured more in his thinking. He remains open to exchanges in and outside the world of improvisation, all the while pursuing a highly personal path through his own composing, arranging and playing that is ever more exciting.